The two “Vs” — also known as V&V, verification and validation — serve to link the medical device product that has been developed all the way back to the initial customer needs and product requirements.

Bill Betten, Betten Systems Solutions

[Image by theilr, via Flickr under Creative Commons 2.0 license]

In fact, the V&V process ties the results back to the initial requirements, but the results also form the basis for a subsequent successful submission to the FDA (or other regulatory body). Verification and validation have a direct influence on the success of your product development effort.

As a reminder, this is the fifth and final article in a series focusing on the definition and execution of product development activities post-funding. It includes the following:

- Idea – Without it, nothing to be developed

- Process – The structure for development

- Plan – The blueprint

- Requirements – The details

- Regulatory / Reimbursement – Critical to the medical device space

- Verification / Validation – The right product doing the right thing (The article you’re reading).

Verificaiton and validation are both elements of the overall testing process. While the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they really demonstrate very different aspects of the product testing process and should be used for the appropriate activity.

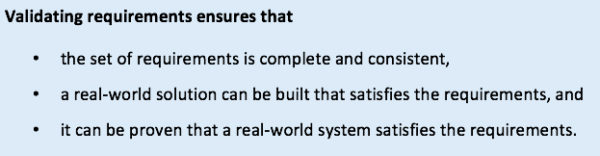

The FDA outlines their expectations in Design Controls 21 CFR 820.30. Design controls are the quality practices and procedures that form the basis for the design and development process and are intended to ensure that the device requirements meet the user needs and the intended use of the product. The V&V processes provide confirmation that this is indeed the case. Verification requires confirmation by examination as well as objective evidence that the output meets the input requirements (21 CFR 820.30(f)). The nearby chart details some of the methods commonly used for verification. These tests are typically performed at the subsystem as well as the full system level as part of the development process. The results of verification tests must be documented and are archived as part of the Design History File (DHF). The test results and documentation are thus part of the submission to regulatory bodies such as the FDA.Validation requires objective evidence that the requirements match user needs and the intended use of the devices (21 CFR 820.30(g)). This is confirmed by objective testing on production units (or equivalents) under actual or simulated use conditions.

Since validation is focused on the user needs, this testing is done as a more cohesive effort near the end of the product development process as the product needs to be essentially completed. Depending upon the classification of the product, validation may encompass clinical testing on production units. These results are also documented and are submitted to the FDA as part of the premarket submission process.Here’s a simple way to remember the difference between verification and validation:

- Verification – Building the system right

- Validation – Building the right system

Building the wrong system in exactly the right way will almost certainly result in market failure, even though all the process steps were followed, and the product verified. Ultimately, the user or the market acceptance will determine your ultimate success. A technical success that doesn’t sell or meet the users’ expectations won’t last long. (Anyone remember Betamax videotape?).

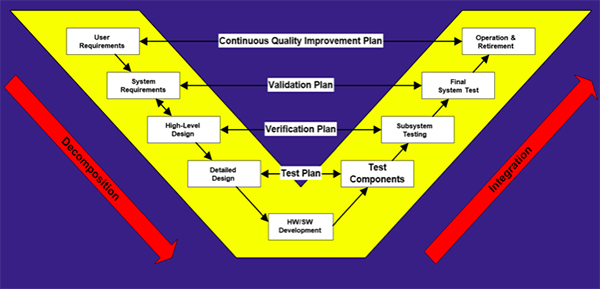

The product lifecycle “V” model, shown below, illustrates the relationship between the various stages of a system development and the test strategy.

Ultimately a link needs to be established between the initial product requirements and the V&V testing, which demonstrates that the user needs and requirements established early in the project and refined during the development process are indeed reflected in the final product. A traceability matrix is the tool that maps or traces the requirements all the way through to the test results. Many software tools for automation of this process are available, but fundamentally a spreadsheet can also work. At its most basic, the format is as simple as that shown below:

| User Need | Product Requirement | Verification Protocol | Verification Record | Result |

V&V testing is generally applicable to hardware, software and systems. In practice, software may be somewhat more difficult to verify and validate as it may be difficult to address all possible test combinations, particularly those related to misuse. In that case, software validation may involve reaching a “level of confidence” that the device software meets all requirements and user needs. In some instances, user site software validation may also be described in terms of installation qualification (IQ), operational qualification (OQ), and performance qualification (PQ).

In any event, the regulation of medical devices and the V&V process help to ensure that, perhaps more than in any other industry, that the end product does what it is supposed to in the environment in which it is intended.

Hopefully, this series has provided a high-level perspective of the complexities and complications of medical product development.

Medical device development is often characterized as anywhere from 60% to 80% documentation. While much of that documentation is driven from a regulatory perspective, it is also generally good engineering practice. From a practical perspective the medical product development process can be summarized as satisfying the need to know:

- What is important and why,

- Why decisions were made, and

- The product does what it is supposed to

…without having to ask anyone!

Bill Betten is the president of Betten Systems Solutions, a product development realization consulting organization. Betten utilizes his years of experience in the medical industry to advance device product developments into the medical and life sciences industries. Betten most recently served as director of business solutions for Devicix/Nortech Systems, a contract design and manufacturing firm. He also served as VP of business solutions at Logic PD, medical technology director at TechInsights, VP of engineering at Nonin Medical, and in a variety of technology and product development roles at various high-tech firms.

The opinions expressed in this blog post are the author’s only and do not necessarily reflect those of MedicalDesignandOutsourcing.com or its employees.

We definitely agree that building the wrong system will result in a failure. That’s pretty much a guarantee in this business. How much do you think these practices differ for startups in comparison to more established larger medical device companies?

I don’t think they vary much in principle and in what should be done. Where they do differ is that the more established larger medical device companies tend to be much more risk averse and have built a Quality Management System that is clearly geared toward mitigation not just of patient risk (normal concern), but that of litigation risk as they are a bigger target and have more to lose. I once had a senior exec at a large medical firm comment that their QMS demanded “1300 documents, when 300 would do.” Perhaps a bit of an exaggeration, but not by much. Small companies also tend to cut corners due to financial limitations, trying to walk the line between doing just enough and too much. Larger companies also typically have a good idea of what their products need to do since much of their product effort tends to be incremental in nature. Start-ups tend to be more disruptive (hopefully) and as a result may not have as an accurate a vision of the product and its market, particularly if revolutionary. Great question, worthy of a lot more discussion.